The most expensive riflescopes marketed to hunters now list for over $4,000, about 10 percent of the cost of a mid-level automobile. In 1926, a 4x Zeiss Zeilvier scope cost $45, or 13 percent as much as Ford’s Model T Runabout. Improvements in scopes and cars are easy to take for granted or to forget during sticker shock.

Optical sights help us aim, but they can only enhance what light shows us. We don’t see a deer; we see light reflected from the deer — or, in silhouette, light behind it.

In basic form, glass is a melt of silicon dioxide (quartz) with calcium and certain alkali. The first optical glass to bend and focus light as well as to pass it arrived around 1884. Credit the Glastechnisches Lab in Jena, Austria, (to become Schott Glaswerke). Dow Jones was then publishing its first stock index and John Harvey Kellogg was earning a patent for “flaked cereal.” Just eight years earlier, George Custer had paid dearly on the Little Bighorn, and William Butler Hickok was shot in the back of the head by Jack McCall at a Deadwood card table.

While crude riflescopes date to the 1850s, receiver-mounted optics came much later. Zeiss had a “prism” scope around 1904, soon after the J. Stevens Tool Co. cataloged riflescopes in the U.S. By Wall Street’s 1929 collapse, Zeiss had acquired Hensoldt and was listing 1-4X and 1-6X variables. The Depression seemed to spawn scope makers stateside. In 1930, Bill Weaver, just 24, challenged the high cost of scopes with his $19, 3/4-inch Model 330. It had internal adjustments: 1-minute windage, 2-minute elevation.

During the next couple of decades, customers paid little for huge improvements in image quality and in scope durability, reticles and adjustments. It was a golden era, sparked by the Zeiss discovery that magnesium fluoride coating cut the 4-percent light loss to reflection and refraction at air-glass surfaces.

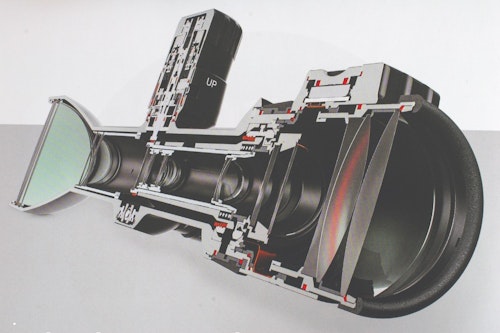

Fog-free scopes came in 1949, when Leupold & Stevens sealed nitrogen in scope tubes. Until the 1950s, W/E adjustment moved the reticle in the field. So engineers put an erector pivot at the rear, where the reticle was. In 1962, a year after Leupold announced its Vari-X 3-9X, Lyman began installing Perma-Center reticles in its All American scopes.

During this time, scope tubes grew in diameter from ¾- to 7/8- to a standard 1-inch stateside. But European and some U.S. makers produced 26mm tubes (bigger than the 25.4mm 1-inch). Steel gave way to lighter alloy. Still, prices lagged. A post-war Zeiss cost just $11 more than its Depression-era forebear; a 4X Unertl in 1950 brought $2 less than a 4X Noske in ’39! A decade later, I ogled the market’s best riflescopes at prices of $39 to $59. As a new Chevy Impala listed for about $2,600 in 1960, a scope cost about 2 percent as much as a car.

Refinements since, with inflation, have hiked scope prices. One-piece tubes, CNC-machined from thick-walled tubing, are sturdier and leak-proof. Heavy horsehair reticles that broke in recoil acceded to Leupold’s Duplex, .0012 platinum wire flattened to .0004 near the center. Meopta’s etched reticle results from UV light striking a template that exposes all but the reticle on photo-sensitized glass. Magnesium fluoride has been replaced by multiple compounds in lens coatings that enhance brightness across several wavelengths. Every worthwhile scope is now “fully multi-coated” (all air-glass surfaces). Meopta applies 13 coatings. On exterior lenses, Zeiss LotuTec sheds water for clear aim in rain or snow. Bushnell’s Exo Barrier also repels oil and nixes breath-fogging. Leupold’s Diamondcoat resists scratching.

Scope interiors are more durable, and W/E adjustments are crisp, repeatable and more precise. A turret dial corrects for parallax (apparent target shift behind the reticle when your eye isn’t aligned with the scope’s axis), while bringing the target into focus. Dial rotation indicators prevent full-rotation error. Illuminated reticles feature multiple brightness settings and automatic shut-off. Trajectory-matched elevation dials cut and scribed for specific loads let you “dial the distance.” (Lasering the target at 600 yards, dial to “6” and hold center.) Increasingly, scopes sell with a buyer-specified TMD dial.

Range-finding reticles went digital in 2018, when Sig Electro Optics announced its BDX system. The shooter transfers ballistic data from a smart-phone app to a BDX Kilo laser rangefinder, then “bonds” a BDX riflescope to that rangefinder. Ranging a target with the Kilo illuminates a dot in the scope for a center hit with dead-on aim. As there’s no laser in the scope, BDX is legal for hunting in all states. Other companies are following Sig’s lead, recently Swarovski with its programmable, bluetooth-friendly dS.

Those are features. Has glass gotten better? Yes. But while many shooters think of glass quality and source, scope makers point out proliferation of glass types and applications, plus strict specifications and close tolerances in lens grinding and polishing. These — with attendant research, testing and patents — contribute most to improved performance. Swarovski, for example, buys “about 100 types of task-specific glass.” Prism flatness is held to 1/100,000 mm, light angles to 1½ seconds. This Austrian firm holds such close tolerances that many are gauged by lasers. Other top-end optics makers have similar standards. Finished Zeiss lenses are so closely matched that they “stick” by vacuum pressure when joined by hand.

Some years ago, Dr. Walter Mergen of Zeiss told me that engineers test not only for the action of glass on light, but also for other lens properties. “We measure elasticity, thermal expansion and conductivity, stain and moisture resistance, the effects of acids. Moisture alone can draw alkali ions, forming a solution that erodes the silica gel layer of the polished surface.” Glass hardness is gauged by pressing a diamond point into the surface. Measuring the cavity yields “Knoop hardness” in kiloponds per square millimeter. Abrasion resistance is gauged by putting a grinder to the lens under controlled pressure for a set time.

Lens surfaces can be spherical or aspherical (the center curvature differing from the periphery’s). “Aspherical internal lenses can yield sharper resolution, a flatter, even a wider field than spherical,” said B&L’s Bill Cross. “In some scopes, these lenses are plastic, which can be molded to shape inexpensively.” Forrest Babcock at Leupold told me costly lenses are typically designed for use inside, where lenses are small and protected. “A big objective lens can account for a quarter of the manufacturing cost of a scope,” he said.

Babcock explained ED glass: “Extra-low-dispersion glass is often joined with a doublet to form a triplet or apochromatic lens. It corrects for overlap of light rays joined by the second lens in an achromat.” A couple of decades ago, a 6-inch blank of ED glass cost about $5,000, or 170 to 200 times as much as a blank of ordinary optical glass. In a big objective, it bumps scope price considerably.

A lot of money goes into the machinery, software and skilled labor needed to produce riflescopes. In its lens production and fitting section, Meopta employs 900 people. Forty coating machines include eight Syrus units worth 1.2 million Euros each! Beyond the glass and myriad other components, manufacturers must “spec” abrasives, bonding agents and coatings, as well as processes. Quality control adds even more overhead.

Even entry-level scopes must reflect well on a brand, as they affect the reputation of all its optics. Once, on an unexpected hunt far from home, I bought a $99 Leupold at a Walmart and put it on a Marlin lever rifle. The image was bright, sharp and color-true. From the bonnet of a pickup, that rifle and its basic 3-9x40 sent three Hornady bullets into a 3/4-inch group.

As in automobiles, you can pay a great deal for brand, size, power and luxury features in scopes. German and Austrian optics — Zeiss, Swarovski, Leica — have a sterling reputation, and the companies charge for it. But such hallowed brands import parts, even scopes to flesh out their affordable lines. Some glass for elite Teutonic names hails from the Far East. “It must, of course, meet strict specifications,” Europeans assure me. And they do. Remember when Japanese autos got a dismissive sniff? What do you think of Toyota now?

Brightness (light transmission) and resolution (detail sharpness) are common measures of optical quality. But in popular text, resolution seldom gets a number. Whether you’re selling or shopping scopes, an eye chart such as your optometrist uses can help you compare resolution. Light transmission numbers are tossed about as irresponsibly as COVID infection rates. How do writers know a scope that claims to pass 95 percent of incident light isn’t delivering 91? They don’t. Over Bavarian amber, one optical engineer assured me 90 percent transmission in scopes and binoculars is very good, and 94 percent is stellar.

Scope tubes of great girth and weight top current price lists. A Swarovski dS 5-25x52 weighs 38 ounces with a 40mm tube. A 34mm Vortex Razor HD 4.5-27x56 weighs 48 ounces. But while optically superb and loaded with features, they can make a rifle burdensome and awkward. They require high and expensive rings. Though they’re popular with long-range shooters, they’re ill-suited to hunting rifles.

“My clients include people with too much money,” said a pal whose custom rifles are among the loveliest objects ever wrought of steel and walnut. “They hunt Africa as breezily as we fetch milk from the grocer. They’re accustomed to having the biggest and best, so they order the most powerful rifles, the most expensive scopes. A 30-ounce optic that runs to 20X makes no sense on a dangerous-game gun, even a .300. The inertia of that scope pulls it free of rings in sharp recoil. The rifle handles like a jackhammer.”

My first riflescope was a 2 1/2X that, had I not foolishly sold it, would have accounted handily for just about all the game I’ve shot with scoped rifles since. But most hunters seem enamored of power — and the instant choice of power. While 3-9x40 variables of the ’60s were truly versatile sights, they were soon eclipsed at market by stronger glass. Then magnification ranges grew. The three-times range of the 3-9X (top power three times the bottom) gave way to four-times (3-12X). In 2007, Swarovski introduced its Z6, a 30mm scope with six-times range. Other firms offer five-, six- even eight-times magnification. In a rare fit of retro brilliance, Swarovski’s Z6 sired the 1-inch Z5. A 3.5-18x44 Z5 weighs less than a pound!

“Wide power ranges aren’t free,” cautions Mark Thomas. After a decade at Leupold, he founded Kruger Optical in Sisters, Oregon, where he and his staff design scopes. “To broaden a power range, you may have to add lenses to correct aberrations. More weight, higher cost, a longer erector assembly.”

Leupold engineers Lance Scrivens and Rick Regan agree. “At five- and six-times magnification,” says Scrivens, “low-power vignetting increases. Maintaining focus and keeping parallax at bay become difficult. Adding lenses and aspherical glass hike expense. When broad-range scopes appeared, following Albert Fideler’s work at Swarovski, their high prices limited sales.”

“Tolerances are tighter than for traditional scopes,” explains Regan. “Figure plus or minus half a thousandth for erector cams. Lenses in a six-times scope travel about twice as far as in three-times sights, so dimensional variation in components has twice the effect.” He concedes new models are the life-blood of any industry. Whether shooters actually need heavy scopes with wide power ranges is a moot point, as long as they buy. Some scopes package impressive power and range in sleek tubes. I’ve used Swarovski’s Z8i 3.5-28x50 on targets to 1,000 yards. It’s a marvelous sight, not as heavy or bulky as the description suggests.

The trend to big objective glass trails the rush to power, prying magnification ranges wider. Front lens size affects exit pupil, the diameter of the light shaft reaching your eye. (EP = lens diameter in mm/magnification). At 6X, a scope with a 42mm objective lens has a 7mm EP, roughly your eye’s maximum dilation at night. Even at 12X, that scope has all the light your restricted pupil can use at noon. Reducing magnification increases EP without the bulk and expense of big glass.

The fast-focus eyepiece is becoming standard on scopes. But like a set of car tires, you don’t need to rotate an eyepiece fast or often. It focuses the reticle to your eye. Reset it when age changes your vision.

Reticles in scopes for U.S. markets have traditionally been placed at the second (rear) focal plane, so they appear one size across power ranges. Front-plane reticles, popular in Europe, “grow” and “shrink” with power shifts. Hard to see at the low magnification you want for shots in cover, first-plane crosswires bulk up at high power, hiding small, distant targets. On the other hand, because they stay one size relative to the target, first-plane reticles make for fast ranging at any setting. Illuminated reticles can speed aim in dark or “busy” cover, but they add considerable cost.

The selection of riflescopes and brand rivalry have increased with outsourced production in Asia. High-quality optics from Japan and the Philippines offer great value. The best buys lie in the fiercely competitive mid-price range, especially in popular offerings like 3-9x40s. At a Cabela’s store last year, I counted nearly 200 scopes on display. Only 13 were priced higher than $1,000. “Great optics,” said the clerk, nodding to that cluster of blue-bloods. “But their rent is overdue.”

If you recall the Eisenhower administration, you might say refinements beyond fully multi-coated lenses, fog-proofing and centered reticles amount to a lot of gingerbread. The most sophisticated scopes retail for 100 times the price of my first scope. Are they that much better? No. But lamenting the dearth of fixed-power scopes at prices of the ’60s won’t bring either back. Besides, scopes are now brighter, more reliable and more versatile. They’re better sights.

Gremlins in modern glass? There aren’t any. If a scope helps win a match or take a recordbook animal on a costly hunt, it will remain a bargain in memory, whatever the price. Remind customers of that after you ask what they paid for their automobile.

For your part, bear in mind that Fords and Chevys, Toyotas and Subarus outsell Mercedes.